By OBI NWAKANMA

It is no longer news: coronavirus arrived in Nigeria duly, and it wears a crown. That’s right. It has proved to be a great leveller. It began its advent from the very top, right there in Aso Rock, where the president’s chief of staff, Abba Kyari, who many believe is the real shadow behind the throne, was diagnosed. Kyari had arrived from meetings in Europe, where many say he had gone to conclude negotiations for an ill-fated $27 billion-plus loan to Nigeria.

He detoured from thence to Egypt, and to a party in Abuja in which many governors of the governing All Progressives Congress, APC, among them the Bauchi State governor, Bala Mohammed, were present. The Bauchi governor was the first to test positive publicly, followed by Abba Kyari who soon fell sick. He was said to have started coughing violently at the National Executive Council meeting in which the president and the vice-president were present.

But out of the party in which many shook hands and broke bread, and whispered closely, came a torrent of covid-19 cases. Many at that party tested positive. Atiku Abubakar announced that his son had tested positive. The governor of Kaduna tested positive and quickly quarantined himself. He may be built like a short dagger, but Nasir el-Rufai acts like a very sharp machete. He came on TV and announced himself positive and self-quarantined. That was a good thing. Proactive leadership. Like him or detest him, el-Rufai gets in front of things boldly.

Abba Kyari is said to be currently very sick. He has not been in great health, in any case. But this coronavirus infection might have great implications for the functioning of this administration, built around a powerful Hausa-Fulani-Kanuri alliance, of which Kyari and Kingibe are very critical arrowheads. As at the time of writing this piece, Kyari was still in a Lagos medical facility.

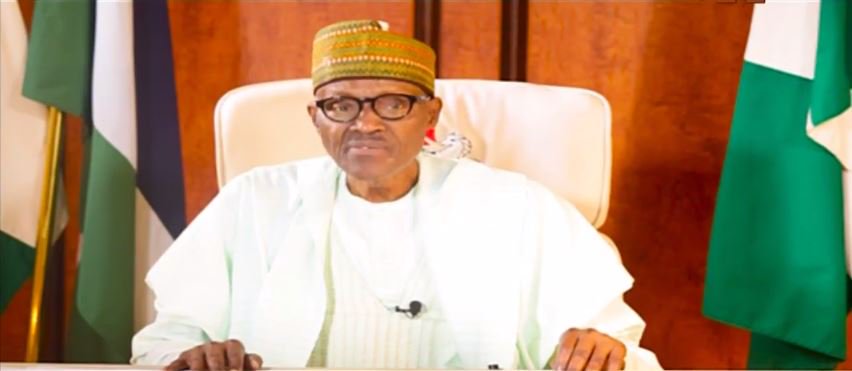

President Buhari had been declared virus-free, as was the vice-president, Yemi Osibanjo. They both went promptly into isolation. The point is that the virus, no respecter of titles or office, has kept a date with Nigeria’s governing elite. That is a good thing. If it only affected the poor, there would be no serious efforts to combat it. It would be known as “the poor man’s disease” and there would be perfunctory response by the government and its inner cabal. But this time, nature has offered us an insight into the hardest truth of all: at our very core, as well indeed at the most vital levels, we are all humans. We eat. We cry. We get sick. We die. We are held by the gross weight of our mortality and we fear that dark, indissoluble night of nothingness called death. Everything else is a mask.

The first reported casualty of the covid-19 virus in Nigeria was a former executive director of the PPMC, a subsidiary of the NNPC. So, the Nigerian government was forced finally to pay attention. It had all the time in the world to get ready for this epidemic. The disease began in China in December and was reported globally. China closed down. The Buhari government did nothing! Soon, the disease began to grow into what the World Health Organisation, by the first two weeks of January, began to describe as the beginnings of an early pandemic. This administration did nothing.

The Nigerian president and his team just sat on their haunches picking their teeth. What occupied them most was how to get a loan that excluded the east of Nigeria, and that would, should the southern politicians not repudiate it, subdue them to economic slavery. Then things, not unexpectedly, went south. It may have started with the president’s daughter who was among the first to be tested and quarantined. It was only when this happened, of course, that President Muhammadu Buhari quickly woke up and rustled together a National Task Force on Coronavirus headed by the director-general of the Nigerian Centre for Disease Control, NCDC, Dr Chikwe Ihekweazu.

Trained at both the University of Nigeria Medical School in Enugu, and the Institute of Tropical Disease of the University of London, Chikwe might seem like one of the few square pegs in their appropriate holes in Nigeria, but the NCDC is, like all Nigerian institutions, badly funded, badly oriented and badly organised. I am not quite sure about the collaborative linkages between the NCDC and the laboratories and scientists at Nigeria’s universities. Only the University of Ibadan Teaching Hospital has a decent, long-sustained virology lab, from what I understand. But there are research facilities, including the ones at Vom’s Veterinary Institute, the Infectious Diseases Centre at Yaba, and so on, which can be quickly pressed to work, even as new labs come on stream. At the point of writing this, I understand that there is a move towards linking them to providing test centres for determining the prevalence of the disease.

It took President Buhari an entire month to respond from when the first known mortality occurred in Nigeria. While the heads of various governments in the world were out taking charge and announcing measures to stem fear, and contain the rage of coronavirus as much as possible, President Buhari went into his shells. Nigeria waited for a very only time to close its borders, create guidelines and establish protocols.

Only on Sunday, March 29, did Buhari come to address Nigerians after much public outcry and only when it is probably already too late in the day. At this point, let me say this, and this is my greatest fear: this administration under Buhari has allowed the virus to enter the population and spread far too quickly that any remedial effort now is frankly a little too late. I say this with the fear that Nigeria is likely to be the major epicentre of the coronavirus pandemic in Africa. Its population is large. Its health facilities poor and its preparedness mediocre. As a result of our social structures and cultural formations, social distancing is nearly impossible. Perhaps what might save Nigeria might be the possibility of what epidemiologists call “herd immunity”.

The coming weeks, as the numbers of the infected inevitably grow, will be both deadly and challenging. Two things actually struck me about President’s Buhari’s Sunday address to Nigerians. One, it offered very little concrete plan with regards to a possible surge in infection; two, it pinned hopes on what scientists and researchers in other parts of the world might discover to cure Nigerians. “We are in touch with these institutions as they work towards a solution that will be certified by international and local medical authorities within the shortest possible time,” declared the president.

But what about Nigerian scientists? What are they doing? Where are the great laboratories? Where are the scientists in federal- and state-funded research centres? Where are the scientists and researchers in the various laboratories in Nigerian universities? Where are the Nigerian military researchers and scientists? The answer might be that a nation which spends far more money rehabilitating the National Assembly buildings than it spends on its universities and its education budget, put together, is doomed. And that is exactly what has happened over the years in Nigeria, and more so under this president. But here is frankly not the time to keep looking back in anger. We have a situation, and it is deadly and dire.

Now, it is urgent for the task force to get the president to federalise all existing laboratories in the nation, constitute a production board, and move fast into the local production of test kits, and the possibilities for a cure locally. All relevant university departments in Nigeria — state, federal, or private —- must be temporarily federalised under a federal emergency act, and provided with funds to expand facilities and undertake urgent research and production.

A Federal Research and Production Directorate, RAP, must be quickly established using the Biafran model.

What is also often lost in all the frenzy is a calm assessment of what happens when a great number of the population get sick, and the public and private health facilities are overstretched as they are very likely to be. There has to be a clear action plan if that happens. I predict a spike in the next two weeks of high morbidity. Two immediate steps need now to be taken: the covid task force should: one, expand emergency training at the various community and township levels nationwide. The task force must create grassroots community action task forces, open up and very quickly prepare to use reconditioned public school halls as both treatment centres, quarantines, and relief distribution centres.

Families must be encouraged to create small isolation and home-care treatment spaces within family houses for isolating and caring for family members who may test positive in case the public health system becomes overwhelmed. Basic training must be provided to some family members on basic care management for sick family members. That way, it might be easy to contain the surge, and also use our traditional kinship systems as voluntary emergency care units. These are strange and trying times. Nigerians must brace for it as they self-quarantine, and as people they know begin to get sick in increasing numbers. But we must also keep our humour. That’s what might save us all in the end. That capacity to laugh at and defy all adversity, including the greatest virus of all: Nigeria’s very incompetent governments.

Nwakanma, a public affairs commentator, writes from the U.S.